Queen Victoria drawing and flight system among over 1,700 missing museum objects

A drawing of Queen Victoria and an aircraft navigational system are among the more than 1,700 items that are absent from museums in England.

Freedom of information requests by the PA news agency to museums and galleries that receive public funding from the Department for Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS) asked for information on missing items from the last 20 years.

This follows the British Museum’s disclosure in August that an unnamed member of staff was sacked after more than 2,000 artefacts were found to be stolen, missing or damaged.

Trustee chairman and former Chancellor George Osborne said records were “altered” by the sacked employee and suggested there was a lack of complete cataloguing at the museum.

Other museums such as the National Portrait Gallery, which reopened in 2023, revealed in the FOI that it has 45 “not located” items.

The museum insists that they are not missing or stolen.

Between 2007 and 2022, a drawing of Queen Victoria from 1869, a mid-19th Century engraving of King John granting the Magna Carta, a bronze sculpture of painter Thomas Stothard and a 1947 negative image of the wedding of the late Queen to the Duke of Edinburgh, were recorded as “not found”.

The gallery said it still needs to complete searches for items following a three-year refurbishment and items recorded as unlocated represent 0.02% of its collection, which houses 12,700 portraits and 164,000 images.

“The bulk of the items currently not located are photographic negatives and for the majority of those, the image has been digitally scanned and is available to the public as part of our online collections database,” the museum said.

The Victoria and Albert Museum disclosed that oil and watercolour paintings, a shadow puppet, false moustaches, various drawings, underpants, stockings and a mousetrap were among its more than 180 missing artefacts.

No descriptions of the items or when they went missing were released through the FOI and the Kensington design institution said it was “standard practice to have a list of missing items as part of our regular auditing”.

A V&A spokeswoman said the museum takes “the protection of national collections very seriously and regularly reviews our security and collection management procedures”.

“This does not mean these objects have been stolen or lost, it might mean for example that a catalogue entry has not been updated after a collection move. Items are regularly recovered as a result of this process,” they also said.

Royal Museums Greenwich, which manages the National Maritime Museum, Queen’s House, the Royal Observatory, Greenwich and Cutty Sark in east London, disclosed that around 245 items cannot be found.

A navigational aircraft computer, a gun-sighting telescope, a cannonball, charts, liquid compasses, an Act of Parliament, an Altazimuth circle, which can be used for holding telescopes, and ribbons and bands for caps were among the collection items revealed in the FOI.

The museum said these could be “ghost entries, the result of data transfer from more primitive databases, incorrect documentation or human error in the past” and it has re-discovered 560 items since 2008 through audits.

The Natural History Museum said a jaw fragment of a Late Triassic reptile, the Diphydontosaurus, was found to have been lost during a loan in 2019 and the next year more than 180 various fish, were recorded as lost and a crocodile tooth was discovered stolen in 2020.

In the last three years, Cichlid fish were lost by researchers while on loan, 20 animal cells were destroyed from documentation not being presented while shipping a collection, and around 24 genomic tissues from octopi and birds were also lost when they were not properly refrigerated according to the museum.

Feathers, muscle, and liver from short-tailed shearwaters and fairy prions from Tasmania, Australia were also destroyed due to not being properly cooled and failing to be present for inspection.

However, as these items were not catalogued, it is not clear how many samples were lost.

A Natural History Museum spokesman said: “We take the security of our collection very seriously, so over the last 20 years we’ve had just 23 instances of lost or missing items from a collection of 80 million, limited to small things like teeth, fish and frozen animal tissue.

“We have robust security measures in place which we regularly review.

“As a world-leading science centre, it’s important that researchers from around the world have access to our collection to help find solutions to the planetary emergency.”

The Science Museum Group also reported two model steam trains, a King George V and a British Railways Standard 4MT class, as stolen to police in 2014.

They had not disclosed the thefts prior to the FOI and the items have not been recovered.

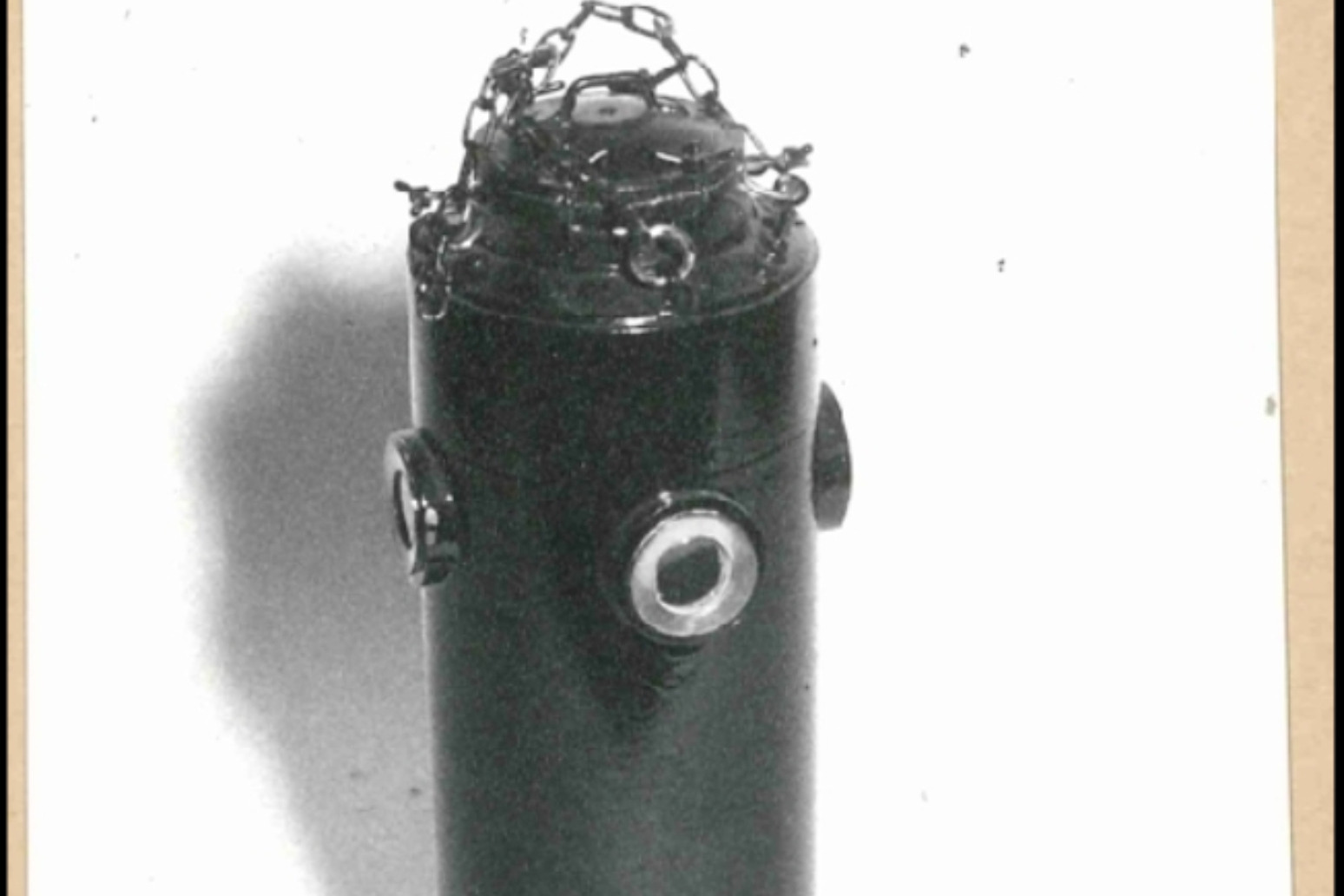

The museum also has recorded a 1960s model of a deep-sea observation chamber, a diver’s watertight torch, a resuscitating apparatus and a 19th-century portrait of Joseph Marie Jacquard as missing.

A spokesman for the Science Museum Group, which houses 425,000 objects across its venues and centres, said it has begun putting barcodes on artefacts to track their locations and keep them safe.

They also said the museum has “resolved many previously identified legacy data issues caused by historic poor practice”.

Some of its collection has been moved from London’s Blythe House to the National Collections Centre at the Science and Innovation Park in Wiltshire, which will be open next year.

The body includes the Science Museum in South Kensington, the Science and Industry Museum in Manchester, the National Railway Museum in York, the Locomotion Museum in Shildon, Co Durham and the National Science and Media Museum in Bradford.

Asked if the DCMS know about the missing items and how they work with museums to safeguard the nation’s treasures, a spokesman said: “We are deeply committed to our world-class museums and the vital work they do to preserve their collections, whilst ensuring they are accessible to the public.

“The department is engaging with all sponsored museums and galleries to seek assurances on their security, collection and risk management arrangements, and are keen to ensure lessons are learned from any incident of theft or loss and shared with other national museums and the wider sector.”

FOIs were also put into the Tate art museums and galleries and the National Gallery, which both reported no missing items and refused to comment on lessons they have learned through cataloguing or enhanced security arrangements.

Horniman Museum and Gardens, which recorded a 1933 protective charm as missing along with six other items, said it has “reviewed” security in light of thefts at the British Museum “as a precautionary measure”.

The Wallace Collection, Museum of the Home, Sir John Soane’s Museum and National Museums Liverpool disclosed only a few missing items.

More than 550 objects, made up of ship camouflage drawings, British Army officer’s private papers, a calendar with a photograph of former Iraq leader Saddam Hussein and currency notes, were disclosed by the Imperial War Museum when asked about missing items.

A museum spokesman said the artefacts “date from many years or even decades ago, long before our current collections management systems were put in place” and “are also typically low-value, mass-produced items”.

In November, an FOI by PA disclosed that a 19th-century cannon from the Royal Armouries collection was stolen from a remote and off-site location.

It was claimed to be a metal theft, meaning the cannon was thought to have been taken for its scrap value, rather than stolen as a “collection object” according to the body.

A pair of mounted sword bayonets, worth £500, also disappeared while on loan from the museum and police officers were called, and as a result other parts of the body’s collection were recalled.

Published: by Radio NewsHub