Low-tech changes 'can reduce airborne Covid-19 spread in emergency hospitals

Simple, low-tech modifications can reduce the airborne spread of coronavirus in emergency Covid-19 hospitals, researchers say.

They suggest low-cost ventilation designs and configuration of wards can reduce the dispersal of airborne virus in emergency hospitals converted from large open spaces.

The University of Cambridge scientists say large air-conditioned halls tend to have top-down air-conditioning, which creates turbulent flows that can mix and spread droplets containing the virus very widely.

In this setting, it may take over 20 minutes to dilute the concentration of smaller droplets produced in a cough to below a tenth of their original density.

According to the researchers, this is enough time for droplets to travel beyond 20 metres, putting healthcare professionals in particular at risk as they move about through them.

Professor Andrew Woods, of Cambridge's BP Institute (BPI), and Professor Alan Short, of the department of architecture, have developed a series of practical solutions to reduce the concentration of airborne virus in buildings converted into makeshift wards.

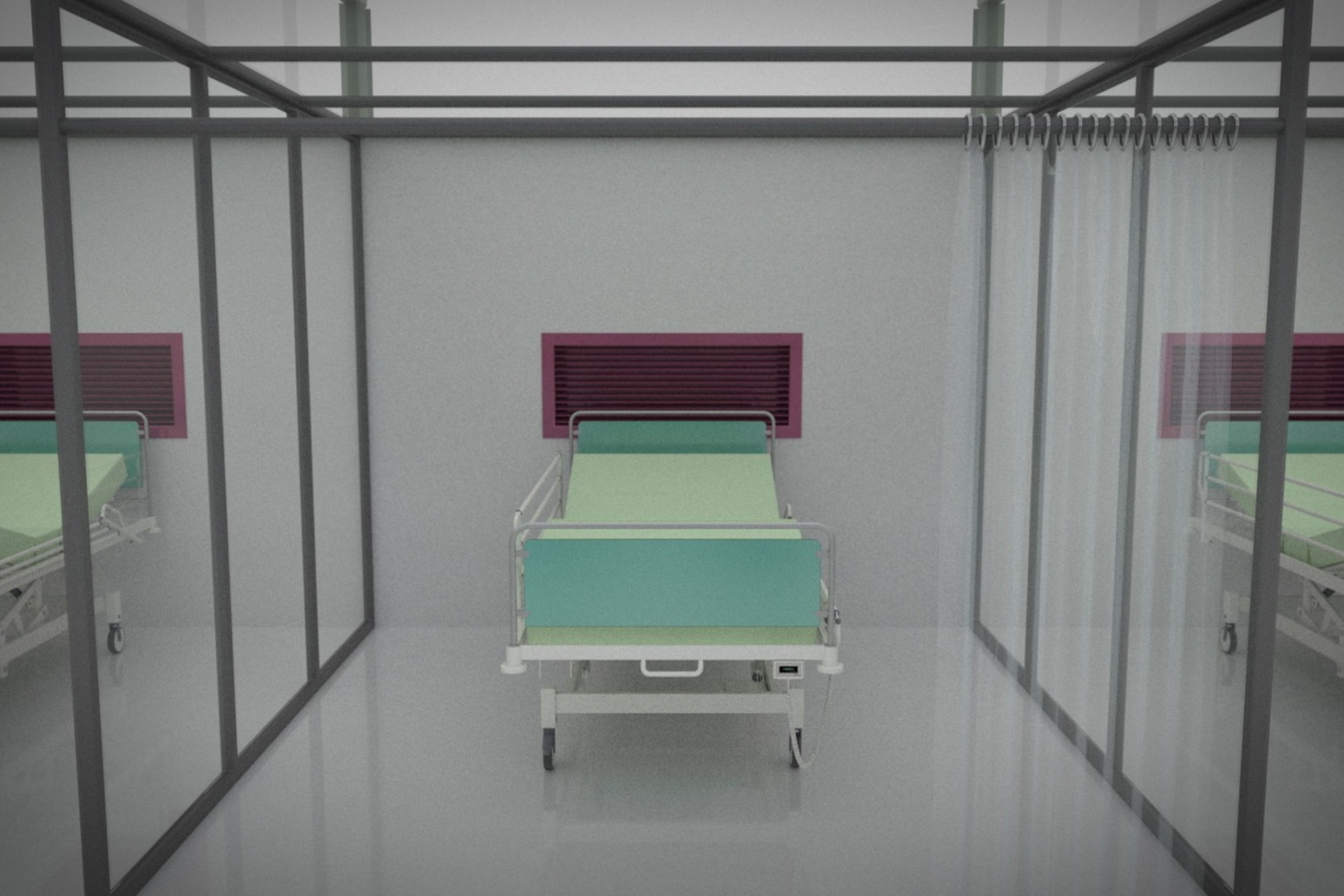

The recommendations include subdividing the large floorplate of a typical hall into enclosed patient zones, a minimum of 16 metres square, with around 10-20 beds separated by solid partitions up to three metres high, and lighter clear polythene sheeting above taped up to prevent air leaking in or out.

Air is drawn through the back of the patient bays by an outflow ventilation duct, removing dirty air from the space and providing a clean corridor space for healthcare workers.

Prof Short said: "Effective ventilation is critically important in helping to suppress cross-infection, and nowhere more so than in an infectious diseases ward.

"Patients coughing or being ventilated will project droplets, some containing the virus, as an aerosol.

"They are so small that they may take tens of minutes to fall to the floor as the droplet evaporates in still air."

The recommendations are based on laboratory experiments that tested ventilation systems for two basic arrangements of beds.

One involves placing hundreds of beds in an open hall with low-level partitions while the other sees beds within enclosed patient bays.

In the completely open version, ventilation air moves down to the ground and spreads out over the patient beds, leading to a highly mixed environment.

When a patient coughs or releases aerosols, the flow pattern of the aerosols can extend across the space to other patient beds, even to patients across the corridor.

The researchers found that in the enclosed bays, the ventilation flow still comes down from the ceiling and moves into the patient bed-spaces and mixes.

However, a good proportion of this air is removed through exhaust ducts located behind the beds.

When a patient produces aerosols within a bay, the aerosol concentration remains high in the bay and air is drawn out through the exhaust duct, limiting the aerosol transport into the main space.

Prof Woods said: "In a large hall, airflows mix up the airborne aerosols all too efficiently and disperse them through the space across patients and, perhaps more significantly, nurses and healthcare workers.

"A small measure such as the installation of part-enclosed patient bays with exhaust ducts can help reduce this dispersion."

The research, which has not been peer-reviewed, was carried out in collaboration with the Interdisciplinary Research Centre in Infectious Diseases, University of Cambridge.

A spokeswoman for NHS England described the suggestions as "nonsense", adding: "Every patient in the Nightingale Hospital is there because they already have Covid-19, and all staff working on wards wear PPE so they are fully protected."

Published: by Radio NewsHub